When historians recount our early days, certain families are central to the story: the Stranahans and the Bryan family certainly. Frank Stranahan, setting up the first trading post and ferry across the river, his wife Ivy for her work in education. Philemon Bryan and his sons Tom and Reed, who were the builders of early infrastructure, including the New River Inn, run by Lucy Bryan, Philemon’s wife.

A third pioneering family should be included in that circle. The patriarch built up the largest independent farm in what is now Broward. He and his wife were pillars of the black community. They sent their six daughters and eight sons to high school, and ten of those on to college. A returning son became one of our most prominent doctors and a local NAACP founder, Dr. Von D. Mizell.

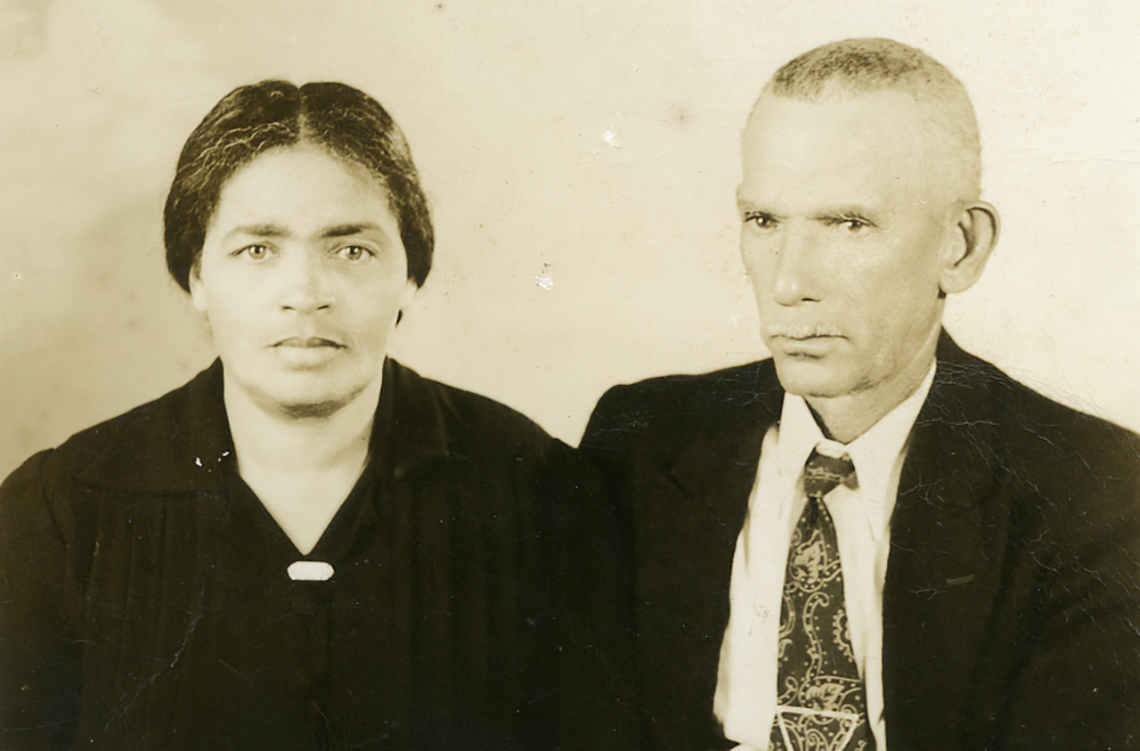

The patriarch was Isadore Mizell, son of a freed slave who moved from North Florida to Dania in 1906. He cleared a plot of land, then planted tomatoes and beans. With his wife Minnie by his side, there was apparently nothing he couldn’t do.

His daughter Ethel Mizell Pappy, who for a time took classes in education at Columbia University, came back to teach in Dania. She spoke of her dad to the Sun-Sentinel in 1986, recalling not only his success in farming but also his savvy in buying and reselling land. They had pigs, cows and a mule. He worked as a carpenter and even as an amateur dentist, pulling teeth for people too poor to see a professional. “You name it, he did it,” Ethel said. According to another daughter, Minnie helped nurse dental patients and others back to health.

Mizell’s largesse was as big as his success. During hard times, he always had food for those in need. He built the first school for blacks in Dania, as well as the first church there. In 1963, the family moved to Fort Lauderdale, where he built a home on NW 15th Terrace.

Critical to the family’s success was Isadore’s respect for education. While he had very little himself, he sent his children off to high school in St. Augustine. Why there? Because in Broward, black teens were taken out of school for up to ten weeks to harvest crops. Isadore and Minnie would have none of that. The results: ten of their children obtained two- or four-year college degrees, five earned master’s degrees and one received a doctorate.

Dr. Von D. Mizell was the eldest. He returned home after his medical studies and set up an office in Fort Lauderdale, soon joining Dr. James Sistrunk and others to found the first hospital in the black community.

But Von, a surgeon, was not the only Mizell offspring making a contribution. Younger brother Ivory Mizell studied theology and photography. He opened the only photo studio in the northwest section, and later joined the effort to stop the winter school closings for black students. Working with the NAACP, Ivory and others finally won the battle in court in 1946. Ivory’s own photography chronicled the lives of the black community. In the summer of 1961, Ivory’s daughter Lorraine took part in the first of the historic wade-ins at Fort Lauderdale Beach, a protest that ended in desegregating the beach.

In addition to Ethel, three more of Isadore and Minnie’s children – son Earl and daughters Bernice and Bryant – became teachers, too.

Leroy Mizell was Isadore’s nephew but was raised in the large family. The Mizells sent him off to college, too, where he studied mortuary science. He later opened the Roy Mizell Funeral Home. It was a struggle in the beginning, as Leroy often had to dig graves himself.

He too was no stranger to the civil rights fight, campaigning for voter registration and co-founding the Fort Lauderdale Negro Chamber of Commerce.

How did Isadore and Minnie produce such an accomplished family? According to Ethel, her father neither smoked nor drank, and he insisted everybody eat dinner together. Minnie made sure dinner was served only when Isadore got home, sometimes as late as 9 p.m. when he had extra jobs. Everybody worked, everybody studied. And they were all at that church he built every Sunday morning.

Clean living and farm fare must have been good for the Mizell pioneers. Isadore died in 1986, at age 103. Minnie lived to be 95, passing on four years later.

As the Sun-Sentinel obituary writer put it when Isadore died, “He lived long enough to see the day when the Dania School for Coloreds he built was no longer needed.”