Not long ago, Lisa Emmott and her husband, Neil, were boarding a flight.

They were flying Southwest, which meant the no-pre-assigned-seats scramble. As they hustled to nab two seats together, Neil joked that he was going to get a T-shirt that read “If you want to keep your kidney, don’t sit next to my wife.”

Or, well, he sort of joked. It’s actually a fairly plausible outcome for somebody who spends several hours sat next to her.

Lisa Emmott wants to talk to you about your kidneys. In particular, she wants to talk to you about donating one. Did you know that kidney donation isn’t just a box you can tick off when you’re getting a new driver’s license? It’s not like, say, a heart – an organ that you very much need and that only gets donated after death. Most folks can get by just fine with only one of their two kidneys. You using the other one? Lisa Emmott wants to know, because she’s got ideas about where it could be put to use.

Last month as she navigated a packed Las Olas Boulevard for Christmas on Las Olas, she wore a green shirt that proclaimed her a “kidney warrior.” Friends, neighbors, other parents at her daughters’ school, strangers who give her even the slightest opening – if you let Lisa Emmott have a moment, there’s a good chance she’ll tell you about how important kidney donation is, and how easily you can do it. She’s a kind of one-woman Uncle Sam poster, pointing out at everybody she meets: “I want YOUR kidney.”

She’s been interviewed, she’s written letters, she’s done whatever she can do to let whomever she can find know about kidney donation. Today she shares her family’s story – her husband’s story – as far and as wide as she can.

For years though, the Emmotts struggled almost completely by themselves.

Before all of this – before the publicity and the waits, before the surgery and the kidney donation evangelism – Neil and Lisa Emmott faced a grim, long wait. Neil was first diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease in 2001. They knew it was a condition that would eventually require action, and they monitored it closely. But tell other people? That wasn’t Neil Emmott’s way.

“I think less than five people in the whole universe knew,” Lisa says. “There was really no need to tell anyone. It’s a watch-and-wait scenario.”

Then in the spring of 2016, his kidney function dropped below 20 percent. The time to act had arrived. Both Lisa and Neil’s brother began the donation testing process – and found they had medical issues that prevented them from donating. The kidney was going to have to come from somewhere else. With his wife, Neil was going to have to do something that doesn’t come naturally. He was going to have to ask for help.

Neil Emmott chooses his words carefully. He speaks with a considered baritone and an accent that years away from his native South Africa has not diminished. From the time he left home to join the army at 16, his life has been one of self-reliance. When he married Lisa, they became the sort of couple that seem to balance each other perfectly; she an outgoing extrovert and he, well, not that.

“She likes to refer to me as stoic and reserved and private – and all those words certainly apply,” he says, putting some of it down to cultural differences between South Africans and Americans. “We don’t approach things the same way; we approach things differently.”

Now though, Lisa’s way – smiling but insistent, putting things out there – was going to have to be the way. When you need a kidney, you’d better start asking for one.

“I’d got from the age of 16 to the age of 54 without really needing anything from anybody,” Neil says. “Although I didn’t mean it, I’d said to Lisa I’d rather pour broken glass into my eyes than go public.”

With permission from Neil to make his situation public, Lisa made that a full-time job.

“It was a big step for us to have to go out of our comfort zone and tell the world that my husband needed help,” she says. “It was a big deal for him to give me the permission to go public with this news.

“When you’re faced with picking out a casket or putting something on Facebook, what are you going to pick?”

Asking for Help

Lisa put something on Facebook. The Emmotts started talking about it to friends, to neighbors, to people in their daughters’ school communities. And the responses started coming in. Schoolfriends from South Africa that Neil hadn’t seen in decades. People the Emmotts considered friends but never would have dreamed of asking.

Teachers. Anybody was a potential lifesaver.

“I don’t know who’s going to be the person to save my husband, and allow my daughters to have a dad,” Lisa says.

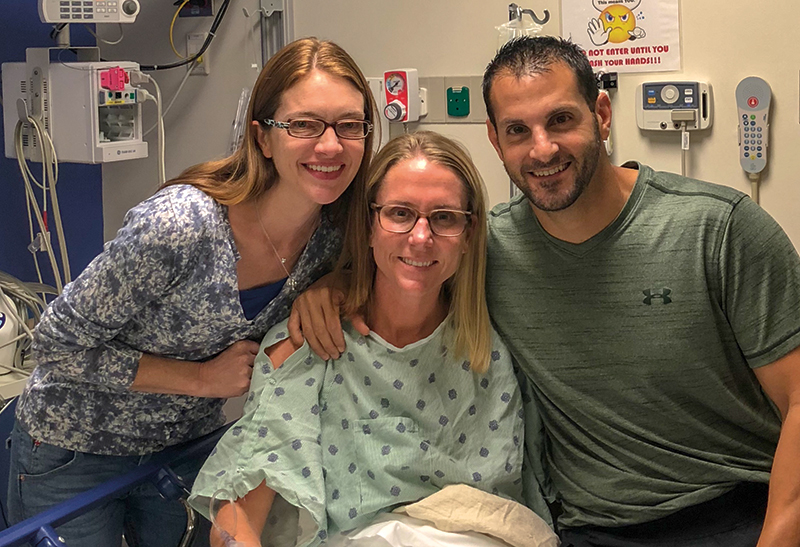

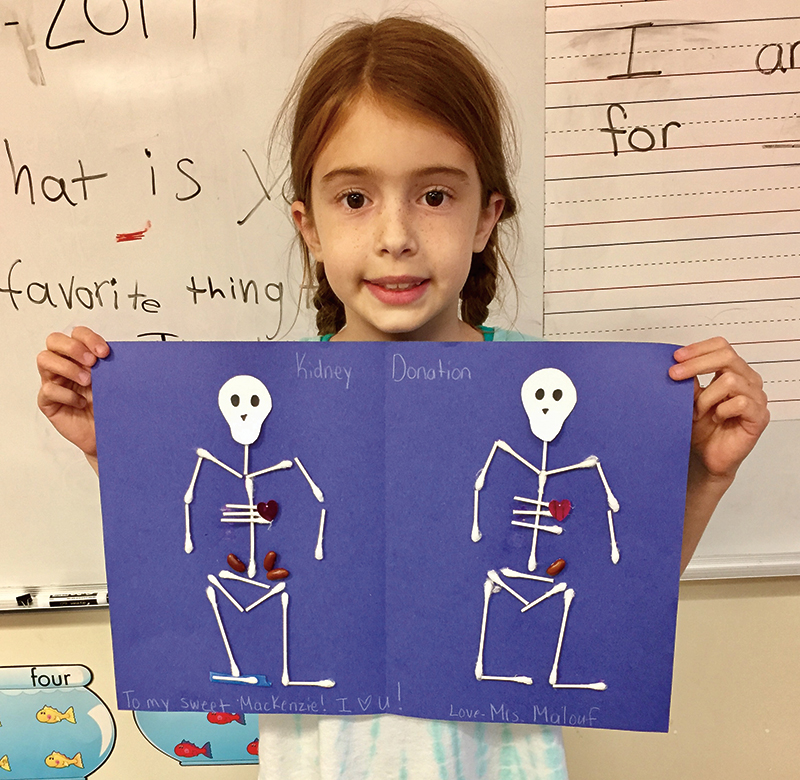

Their daughter Mackenzie was in first grade at Bethany Christian School; Lisa told her teacher, Allison Malouf. Malouf, who now teaches at Calvary Christian Academy, had been interested in kidney donation since her husband donated one nearly a decade ago.

“I knew all along that I would eventually donate my kidney,” Malouf says. “I knew that one day, on God’s timing, I was going to donate my kidney.” When Lisa Emmott said she needed help, Malouf was ready.

Lisa also mentioned it to another teacher, her close friend Britani Atkinson. Both teachers began going through the tests and screenings – and both found they would not be a match for Neil. Malouf had a different blood type, while Atkinson’s kidney was smaller than his. But the pair weren’t deterred.

Lisa Emmott describes the National Kidney Registry as kind of like a dating website, but for kidneys. You (or medical personnel on your behalf) scroll through other people’s perfect kidneys, looking for that one that’s just perfect for you. “You’re looking for a diamond in a sea of cubic zirconia,” Lisa Emmott says. “But they’re out there.”

One way of getting into this internal organ dating pool is via the registry’s exchange list. Potential donors who are incompatible with the person they’d like to donate to instead get on the list. Chains of donors get formed as kidneys are paired with compatible matches until everybody on the chain is taken care of.

In the end, both Malouf and Atkinson donated kidneys; it was Atkinson’s donation that started off the chain that led to Neil Emmott’s new kidney. In September 2017, he flew to Johns Hopkins to receive a kidney that was coming in from California. Atkinson went up for surgery at the same time; her kidney was sent to Boston.

“In that exchange, everybody’s got a purpose,” Neil Emmott says. “Two people that were completely cleared to donate but were not compatible with their intended recipient just got into this algorithmic pool.”

If you’ve got pity to offer, you can take it somewhere other than his door. For him, asking for help had been hard. Receiving it had been humbling.

“You always hope that in your circle of friends there are people who are prepared to do for you what you are prepared to do for them,” he says.

It was a process that involved fear, pain – and finding out how many people were willing to put their hands up for him.

“It was hard,” he says. “And good.”

Crossing the Bridge

In November, Lisa Emmott flew to San Francisco to meet a woman she’d only ever spoken to on the phone. The Golden Gate Half Marathon was the following day, and Lisa was running in it. The other woman, her running partner for the day, had driven up from Los Angeles. When they met, Lisa was trembling all over.

Neil had already met Shannon Bousfield, the woman whose kidney now resides in him. They’d reached out to each other shortly after the surgery. Donators and recipients each have the option of being contacted or remaining anonymous; both Neil and Shannon wanted to hear from each other.

“It does take a bit of networking,” Lisa says of meeting a donor. “We thought it was a man. They’re really not allowed to tell you anything. We were told a man, 43, at UCLA. Turns out it was a woman.”

Not long after, Neil went on a business trip to Los Angeles, and they met. Now Lisa wanted to meet the woman who had saved her husband’s life. Through chatting online and on the phone, Lisa had found out Shannon is a runner; less than a year after donating her kidney, she’d run a half-marathon personal best.

Lisa is very much not a marathon runner. She had started walking to alleviate stress during the difficult times, and that had morphed into jogging, but she’d never done a big race. She wanted to run to honor Shannon, so she thought maybe she’d do a 5k.

Her daughter Cameron was not impressed. What kind of a tribute is a 5k? C’mon mom, do a half-marathon.

Which is how Lisa Emmott found herself hugging the woman with whom she would soon run across the Golden Gate Bridge.

“Meeting the stranger whose kidney now sleeps in my bed at night and sits at my dining room table, that was a unique and once-in-a-lifetime experience,” Lisa says.

“I hadn’t really been nervous about meeting her … but when she drove up, I felt like I was a little kid at Christmas; you kind of know what’s going to happen, but until the moment is actually there…

“She only has one kidney and my husband has the other one. That is pretty amazing.”

That amazing feeling has been replicated elsewhere. For Allison Malouf, the feeling came after months of disappointment.

“You know there’s a chance your recipient might not reach out to you,” she says. But when she sent a letter, then another, then another, and never heard back, it was hard.

“I was very hurt, I’ll be honest,” she says. “I was upset.”

Then last summer, she sent another, short letter. One more shot. More months went by. Then one morning, she checked her email and found a response.

“I literally just bawled,” she says.

In December, she flew to San Diego, where her recipient lives.

“She is amazing, and she is doing well,” Malouf says. “And, come to find out, it was just a lack of communication. She hadn’t received my letters. She had sent a letter, and I hadn’t received it. Now we have met and she is like family. She’s like my mom.

“All along, I just wanted to make sure that they’re OK, that they’re happy and healthy and living the life that God intended for them.”

Meanwhile in San Francisco, Lisa and Shannon ran the half-marathon. There were times, Lisa says, when Shannon could have run on and met her at the finish line. But she stayed with her, and the pair finished the race holding hands. Lisa’s still a bit amazed she pulled it off. “Neil getting a new kidney was science,” she says. “Me running a half-marathon – that was a miracle.”

Before the race, the pair had talked about places they might meet and races they might run. Lisa’s glad they settled on San Francisco and the Golden Gate Half Marathon. The famous bridge that gives it its name and part of its route is, famously, often shrouded in fog.

“Our entire journey was exactly like that,” she says. “There was no end in visible sight. I just had to keep putting one foot in front of the other and trust that the bridge would catch me.”

For Neil and Lisa, the bridge worked. They entered into a system and a world they knew next to nothing about. They emerged at the other side with a new life – and with new friends who are intimately tied to that life. It’s a journey that began because Lisa couldn’t donate her own kidney to her husband. And for Lisa, it’s a journey that continues – which is why if you happen to meet her, let’s say at the Galleria or on Las Olas, you might find yourself talking about the ease and importance of giving up one of your kidneys. That’s Lisa’s work now.

“I will never be able to donate a kidney,” she says. “But I will always donate my voice.”

For more information on organ donation, visit the website of not-for-profit Donor to Donor at donortodonor.com or email Lisa Emmott at lisa@donortodonor.com. In February, Lisa Emmott will run the Fort Lauderdale A1A half-marathon to raise awareness of kidney donation. She is also helping Donor to Donor set up an informational booth at the event.