When Alan Garber walked into Jorg Hruschka’s office, he didn’t know much about Little Free Libraries.

Garber had been put in touch with Hruschka, the City of Fort Lauderdale’s chief service officer, after calling the city’s Neighbor Volunteer Office. If you want to volunteer your time improving Fort Lauderdale but you don’t know where to start, Hruschka’s a good man to talk to.

Garber, an involved dad whose kids were now grown and out of the house, talked about how much he enjoys helping kids. Hruschka talked about the importance of reading for young elementary school students.

“What I learned from him is that kids learn to read to third grade, and then after third grade they read to learn,” Garber says. “If kids don’t learn to read by third grade, they fall behind.”

From that meeting, a plan formed. Little Free Libraries had already come to Fort Lauderdale, but they were about to become a lot more prevalent.

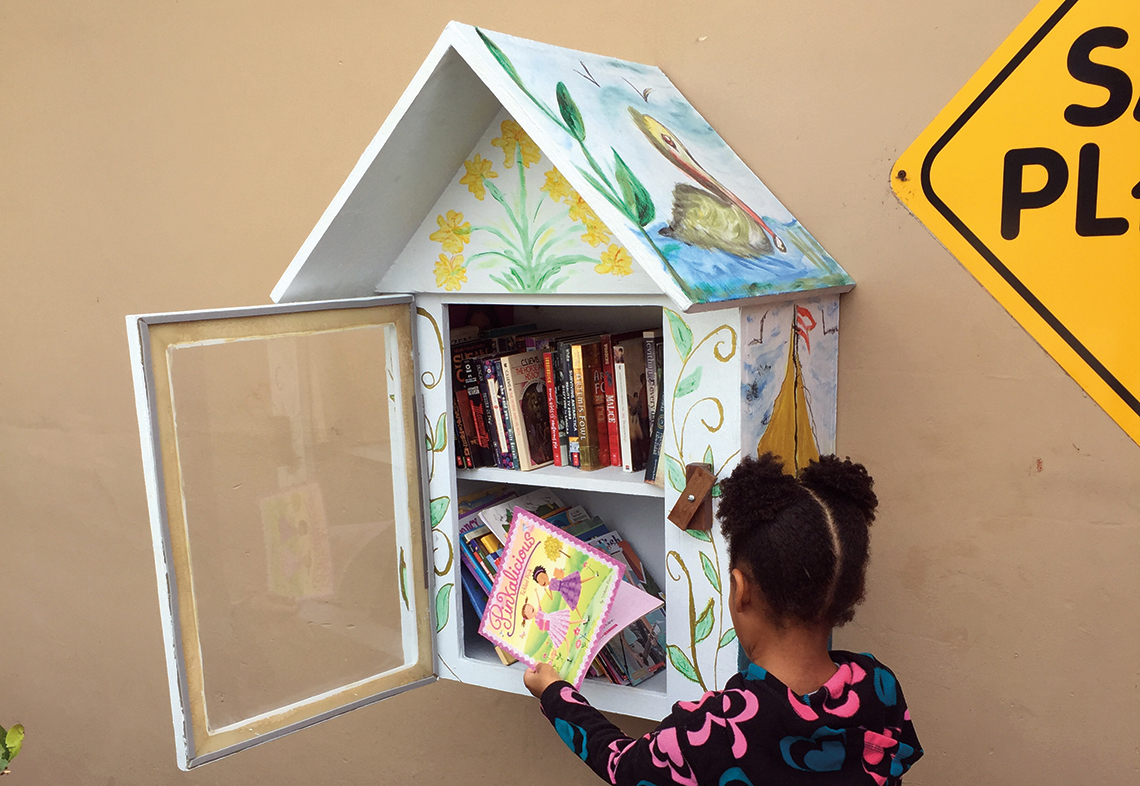

You’ve likely seen a Little Free Library. It’s an international movement with a simple concept – plant a small structure in an area where people need books. The structures tend to look a bit like large birdhouses, only with large glass doors opening onto a shelf of books. Volunteers paint them and then, once they’re open, restock books as needed.

For Garber, this was perfect. He started calling people and posting on Facebook. They put the call out for books and soon had 20 boxes worth of books. Garber set up a not-for-profit organization, Action for Literacy.

Three years later, the group’s volunteers have installed about 75 of the tiny libraries across Fort Lauderdale. And they’ve made a point of putting them in areas where they hadn’t always gone.

When little libraries first started getting installed around the city, it was the city itself that did it. One thing Hruschka noticed was that while the city’s Parks and Recreation Department did a great job putting up the little libraries, they put them in parks – and frequently in more middle-class or affluent places where local children already had good access to books. He wanted to take them into the city’s “book deserts.”

“Originally, it was a convenience to park-goers,” he says. “The city put it into parks in 2014. Two years ago we shifted the focal point.” What started as convenience has shifted into literacy intervention program. “We would like to have 70 percent of children’s books in there, 20 percent of cookbooks and self-help books, and 10 percent of adult books.”

At Fort Lauderdale elementary schools in more affluent eastside areas, Hruschka says, reading statistics look good. Go in to an elementary school like Virginia Shuman Young, Harbordale or Bayview and you’ll find that the percentages of kids whose reading skills are satisfactory or better are in the mid-80s to low 90s. Go into an elementary school in a more economically deprived part of the city, and you’ll find numbers in the 20s.

Regular libraries are great, he says, but it’s also good to create something where there’s no chance of a fine. And anyway, you can put Little Free Libraries in more places; Hruschka would like to make it so that any child in the city can travel less than a mile to find one.

“It’s early literacy intervention,” Hruschka says. “Let’s make sure no child has to walk more than 10 minutes to get a book.” They haven’t quite got there yet, but as they close in on 80 in the city, they’re on a good pace.

Of course, installing a little library isn’t the end of the work. You’ve then got to make sure you’re keeping it stocked and restocked with books.

“I reach out, and I spend my days trying to look out for books,” Garber says.

One time he saw somebody online selling 20,000 books. He reached out and convinced the person to sell them all for $400. He paid the money, Hruschka found a truck, and they hauled all 20,000 to their storage facility, from where they started getting them out to the kids who need them.

Getting the books is one thing. Then there’s keeping the libraries running.

“We always reach out to people to be the ambassador for the library,” Garber says. This is a person who lives nearby and can let them know when the library’s running low. The person who can make small repairs when necessary.

They also try to make a big deal when a new one is installed – get the community involved, give it a paint job with some fun artwork, give people ownership over it. If 50 people put a paintbrush to one, that’s 50 people who will consider it partially theirs.

“It’s organic, community-driven,” Hruschka says. “The more people who can touch the library, the better it is.”

Right now, there’s a core group of just a handful of volunteers keeping Action for Literacy going. But there are plans for more. Garber’s spoken with another organization about taking the program countywide.

“Think about the magnitude,” Hruschka says. “We take for granted that we can read.

“The concept of using (Little Free Libraries) as a literacy intervention program…It’s an exciting concept. It’s something that’s catching on.”