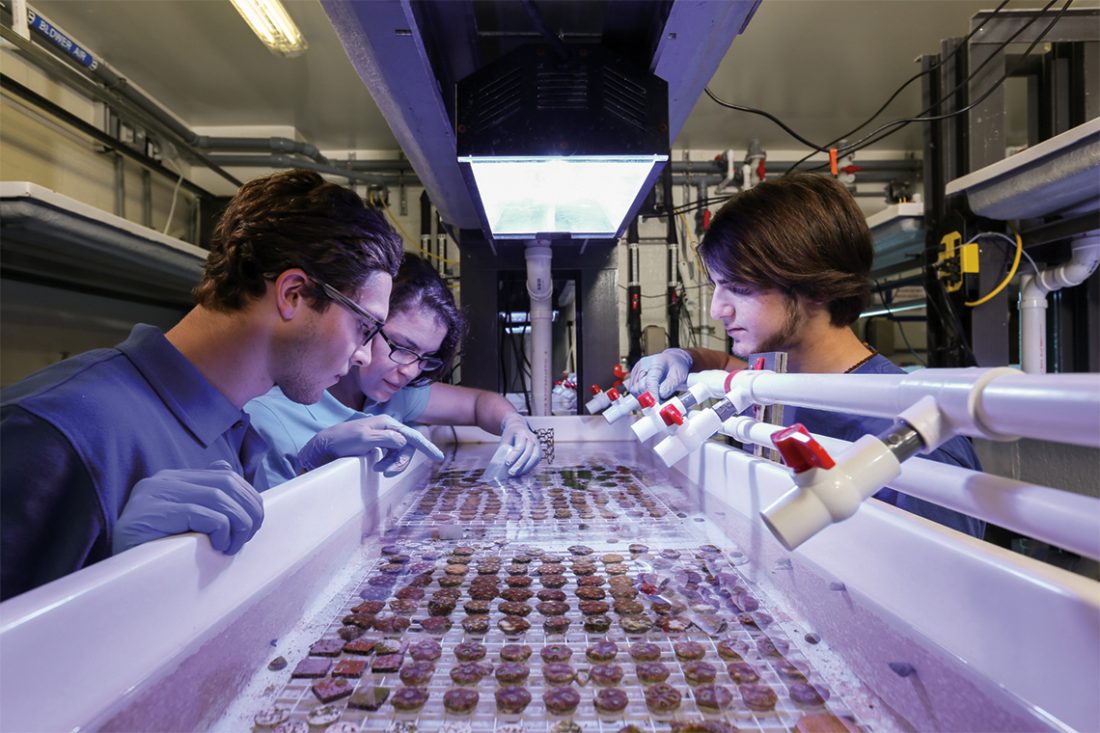

Private support of marine science is apparent at the handsome waterfront research center named after artist, scientist and entrepreneur Guy Harvey. His signature paintings depicting sea life animate the hallways of NSU’s Guy Harvey Oceanographic Center. Located across from Port Everglades at the sandy northern tip of A1A in Hollywood, the center is a hive of laboratories with signs outside identifying the research subjects inside: invertebrates, microbiology and genetics, deep sea biology and coral restoration, among many others. A research institute within the university’s college of natural sciences also bears Harvey’s name.

“In terms of expansion of facilities, we’re looking into adding a new laboratory, classroom and research area in the newest facility, the Guy Harvey Oceanographic Center building,” Dr. Richard Dodge, dean of NSU’s Halmos School of Natural Sciences and Oceanography, said in an email exchange.

“Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography is home to several research-based institutes, such as NSU’s Guy Harvey Research Institute, the National Coral Reef Institute and the Save Our Seas Shark Research Center,” wrote Dodge, who also serves not only as dean of the college but also as executive director of the National Coral Reef Institute.

Dodge ended his email with a pitch for help: “Last but not least, we’re also looking for anyone who would like to help sponsor renovations/repairs to our research vessels, or if they have a ‘gently used’ vessel (29-foot or larger) they’d like to donate for our researchers and students to use. We’d definitely welcome that opportunity.”

Nova Southeastern’s growth plans – and need for money – are not uncommon across South Florida. Even the University of Miami’s venerable Rosenstiel School, which turns 75 in 2017, has more scientific potential than support. “We are always starved for funding for research. We can do much more research than we really can exploit,” says Roni Avissar, dean of the Rosenstiel School. “We have extremely powerful potential here at Rosenstiel, and we compete very well for funds. But not enough for the research that needs to be done.” An imbalance of brainpower and budget also limits the marine research potential of younger South Florida schools active in the field – including Nova Southeastern University, Florida Atlantic University and Florida International University.

Nevertheless, South Florida has emerged as a major hub of marine research that runs not only on federal funding but also private philanthropic support. Now local and regional business and civic leaders want to make the region better known as a hub. Doing that could, among other things, make the money flow more freely.

The annual Fort Lauderdale International Boat Show could provide a potent platform for promoting marine research throughout South Florida and generating hefty donations and other forms of support, if not yachts on loan.

“We connect to the greatest entrepreneurs in the world when our boat show happens. Those guys love the ocean, they love the environment, and they all want to make the world a better place,” says Phil Purcell, executive director of the show’s owner, the Fort Lauderdale-based Marine Industries Association of South Florida, a trade group that represents marine business interests. He sees a chance for South Florida’s marine research institutions to ride a broader wave of private philanthropy.

“Warren Buffett challenged the wealthiest in the world to give away half their wealth, and they’re doing it.”

With greater support, South Florida universities could build on their reputation as a unique cluster of marine research centers, Purcell says. “We can brand this whole region,” he says, not just through research on how to adapt to such scary threats as sea level rise, but also through medical discoveries that often arise from marine science.

“Why do certain things regenerate, like starfish? Why are sharks and rays not prone to cancer? You’ve got 6,000 species that live on a reef. We don’t know enough about them,” he says. “The medical research is out there, whether it’s Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, stem cell research. Nova grafted coral into bone cancer patients. I mean amazing things.”

Bob Swindell, president and chief executive officer of the Greater Fort Lauderdale Alliance, says the business promotion association may organize an informational presence at this year’s Fort Lauderdale Boat Show in November to tell visitors about marine research activity in South Florida.

“It’s connecting the philanthropy with the science. There’s a lot of interest in doing that, whether it’s human medicines or the health of the oceans themselves,” says Swindell, who credits Purcell with identifying the potential for promoting South Florida’s marine science sector.

“November is coming up pretty quickly, but I think we could start to raise the flag” and begin building better awareness of marine research in South Florida at the upcoming boat show, Swindell says. “We may try to do a ‘Did you know?’ type of thing.”

The Greater Fort Lauderdale Alliance also has considered staging its own event to showcase marine research. “Almost like a Davos for the oceans,” Swindell says, referring to the prestigious annual conference of global business leaders in Davos, Switzerland. A marine research conference in South Florida could also put a spotlight on scientists who work outside the tri-county region, including those at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute in Fort Pierce.

“I’ve worked with Harbor Branch up in Fort Pierce where, of all things, they’ve learned to culture conch pearls,” Swindell says. “Before they had never had a conch in captivity that could create a pearl. There’s a professor up there who did it. She is the first researcher in the world able to artificially get conchs to create pearls.”

Sounds like a moneymaker, right? Well, not so fast. “She has to create a new pearl standard that doesn’t exist out there in the gemological world,” Swindell says. “That’s part of what she’s going to need to do to make it viable.”

He says Harbor Branch scientists are trying to develop less addictive painkillers by researching poisonous snails: “Their venom is a phenomenal pain analgesic that has none of the addictive challenges that opioids or anything else has.”

However, not all snail venoms have that analgesic quality. “Some venoms do, some venoms don’t,” he says. “So identifying those specific venomous snails is challenge number one. Then being able to synthesize those venoms in a lab is a big challenge.” Despite the challenges, the potential upside of such discoveries can be a money magnet for South Florida’s marine research universities.

The University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School conducts about $50 million of grant-funded marine research annually, far more than FAU, FIU and NSU. Only the Scripps Oceanographic Institute in Monterrey, California and the Woods Hole Institute in Rhode Island chew through a larger annual amount of research grant money, according to Avissar, Rosenstiel’s dean.

“Roughly speaking, we have about 200 research projects going on right now at the Rosenstiel School,” Avissar says. “One of the biggest current projects we have came from BP as a result of the Gulf disaster.” UM is studying the impact of the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico on fish populations, plus oil dispersion technology.

The federal government historically has been the dominant source of research grant revenue at Rosenstiel. “Fundamentally it was built on research grants that we received from federal agencies,” Avissar says, citing, among others, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Science Foundation, NASA, the Department of Defense and the U.S. Park Service. “We also have a little bit of private funding,” Avissar says.

FIU does about $10 million of annual marine research. NSU’s Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography is working its way through a $37 million, multi-year backlog of active research grants.

Swindell says South Florida’s marine research universities produce myriad studies but focus on their unique strengths. “They tend to be academically competitive, which is fine,” but in their marine research activities, “I don’t see a lot of overlap. I see complementary effort.”

The Alliance CEO also sees opportunities for universities to commercialize their marine science by helping private businesses. Swindell cited a Fort Lauderdale company exploring the installation of electricity-generating wind turbines at sea. “Right next door at NSU, you’ve got coral research. If we have to anchor those turbines, how is that going to impact corals? How is that going to impact life on the sea floor? They could work together and say: OK, how do we cause the least amount of disruption and produce the maximum benefit?”

Marine research in South Florida covers countless subjects. At Florida International University, for example, “we have greatly expanded our shark team,” says FIU spokeswoman Jo Atkins. The university is now leading a three-year shark-census survey that Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen funded with a $4 million donation.

“We have a myriad of other things going on related to fisheries, reefs, ocean acidification, oil spill research in the Gulf of Mexico. We also have a researcher here who does just oddities in the ocean: monster larvae and glowing shrimp and things like that.”

Michael Heithaus, executive director of the FIU School of Environment, Arts and Society, said the university’s diverse marine research has a common thread: “The unifying theme of most of it is coastal ecosystems.”

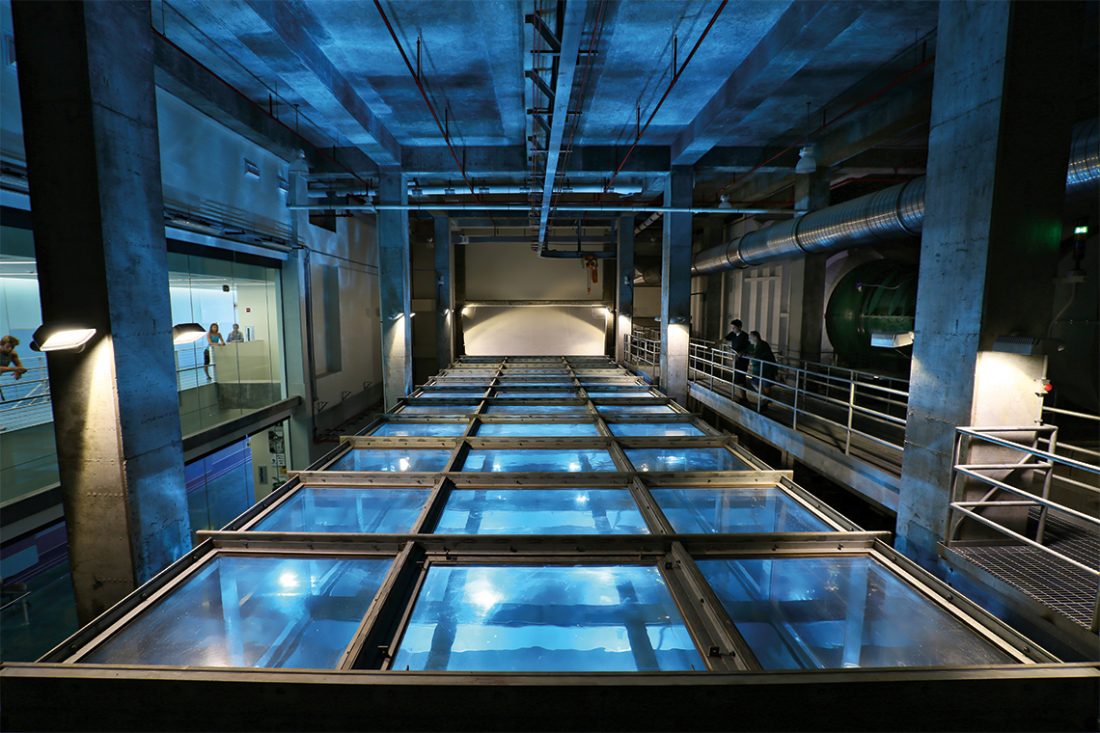

To further that mission, FIU took over an underwater reef research center off Key Largo, called Aquarius, with funding in the form of a $1 million donation from multimillionaire Manny Medina, who led the sale of a Miami-based public company called Terremark to Verizon in 2011 for $1.4 billion.

Heithaus said Aquarius, once owned and operated by NOAA, serves multiple missions. “It not only helps us with marine biology and chemistry research but also helps with training for the Navy and provides a platform for industry – to test equipment underwater, for example,” he said. “Our plan is that we’ll be expanding on that program considerably. Aquarius provides scientific and training opportunities as well as education outreach opportunities that are pretty unparalleled.”

Only certified scuba divers can visit Aquarius, designed for human habitation for days and weeks at a time. “When you’ve got a porthole to the reef for a kitchen window, it’s pretty awesome,” Heithaus said. A cable connecting Aquarius to its landside facility provides power and communications, and “usually the internet speed underwater is better than a lot of places topside,” he said.

FIU is leading a three-year, shark-census survey that Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen funded with a $4 million donation.

Private support of marine research takes other forms, too, not just seven-figure donations from the 1 percent. For example, several South Florida charter boat operators appeared together in June on a panel at the Rosenstiel School to discuss ocean acidification, a process that can destroy fish habitats by dissolving coral. Acidification occurs as oceans absorb carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Several panel members said they had only recently learned about ocean acidification and planned to make other fishing business owners aware of it. “I didn’t know anything about it,” said panel member Captain Ray Rosher, who runs a business called Recreational Fishing Charter. “I would venture to say very few fishermen know anything about it.”

But the panelists agreed almost nobody observes the ocean as closely as they do and that their charter customers are a captive audience for marine science lessons. “We can really inform the average consumer,” said Captain Eric Cartaya of Divers Paradise.

“Ocean acidification is just a symptom of two centuries’ worth of putting carbon emissions into our atmosphere,” U.S. Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, R-Miami, said in a luncheon speech at the Rosenstiel School.

Ros-Lehtinen, a member of the first-ever bipartisan caucus in Congress to address climate change, also said at the luncheon that she is co-sponsoring a coral-preservation bill called the CORAL (Conserving Our Reefs and Livelihoods) Act. “It expands the focus of the law from coral conservation, which is good,” she said. “It also gives federal agencies the authority to play active roles in restoration and recovery.”

Marine research in South Florida appears unlikely to recede as long as the world remains about 70 percent water. Indeed, sea studies may proliferate as environmental concerns, business priorities and politics become more tightly intertwined in South Florida.